Alasdair Macleod: Yesterday, the FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee] released its June statement which only served to remind us that its members are powerless in the face of inflationary conditions. They refuse to accept the price consequences of monetary inflation, still clinging on to an increasingly untenable hope that price rises are “transitory”.

The fact of the matter is that the world is now awash with excess money, the two greatest inflationists being the Fed and the Bank of England. In the US, the Fed’s $120bn monthly QE continues to goose financial asset values, while the US Government has spent a further trillion into circulation from its general account at the Fed. This tidal wave of money threatened money market funds totalling over $4 trillion with negative rates, thereby “breaking the buck”, which is why the Fed has increased its outstanding reverse repos to $721bn.

Interest rates will have to increase far earlier than the Fed admits to stop foreigners dumping dollars, not just for commodities which have nearly doubled since March 2020, but for other currencies as well.

Welcome to the everything bubble, whipped up by American and British neo-Keynesian policy makers who are now increasingly cornered by their own monetary fallacies.

Introduction

Courtesy of the central banks, the world is enmeshed in an everything bubble. We used to be most aware of the Bank of Japan’s extraordinary money printing to corner the Japanese ETF market — but that is no longer a topic of conversation. The Bank of Japan now owns about ¥48 trillion invested in ETFs ($447bn), the most aggressive money-printing stock ramp in the style of John Law and his Mississippi bubble relative to the size of the market in modern times. But today’s monetary planners have dismissed empirical evidence of any dangers as pre-Keynesian, and therefore irrelevant.

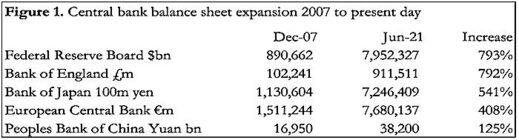

Anyone who hoped that the inflationary response to the financial crisis of 2008/09 was to be just a one-off event will have been sadly disillusioned. And anyone who thought that China, or Japan with their money were the most irresponsible nations — a common perception not long ago, would have got that wrong as well. Even the ECB looks relatively moderate, compared with the British and Americans.

Of course, as well as the expansion of central bank balance sheets there are other factors in monetary policy which we can with justification label as inflationary. But it is interesting that the Bank of England’s chief economist has chosen this summer to leave the Bank, deciding at the same time to no longer toe the official line about rising prices. While some of his colleagues on the Monetary Policy Committee have only recently been rooting for negative interest rates and from the Governor down are now claiming that increasing prices are only temporary, Andrew Haldane appears to be ducking out. And one wonders why sterling is not weakening with the dollar, given the Bank of England’s solidarity with the Fed in terms of common monetary policies. The message from Figure 1 is that sterling, which rallied from $1.15 on the back of dollar weakness to 1.41 currently, should not have rallied much at all — particularly as the perceived value of the Brexit dividend is being superseded by the economic effects of Covid and its extended lockdowns.

Evidenced by the launch of a €1 trillion Covid stimulus package this week, the destruction being wrought by the ECB is economic as well as monetary. The effect is to keep Eurozone bond yields suppressed (read this as mispriced), with even bankrupt Italy sporting a sub-1% ten-year government bond yield. We all know, or should know, the true purpose of this stimulus, and that is to fund and further facilitate the future funding of profligate Eurozone governments. Don’t be surprised if productive businesses get none of it. And presumably, without the Bundesbank’s monetary conservativism the ECB would be issuing even more euros.

China comes out of this comparison relatively well. The expansion of the PBOC’s balance sheet has been the smallest in percentage terms by a long way, its government debt to GDP ratio is the lowest by degrees of magnitude, and the PBOC’s policy planners have been putting the brakes on credit expansion for the best part of a year. This suggests that the yuan is significantly under-priced against dollars, with the future potential to attract inward capital flows, seeking to escape from the declining currencies of the more profligate nations…

We should bear China’s different approach in mind, because the geopolitical consequences of a stronger yen becoming attractive for international capital flows will lead to an obvious contrast between the US impoverishing its population through currency debasement, while the Chinese enjoy an improving standard of living. Furthermore, unless Americans suddenly decide to decrease their spending and increase their savings, China’s trade surplus with the US will continue to increase. Despite the slowing monetary growth reflected in GDP numbers, the Chinese appear to be in a far stronger position than their Western counterparts, both economically and monetarily.

The consequences of monetary expansion everywhere are bound to lead to rising prices, reflecting the loss of purchasing power for diluting national currencies. So far, use of tightly controlled consumer price indices to hide the evidence has concealed the true extent of rising prices, providing goal-sought answers of approximately two per cent all round. But so formidable has the monetary dilution since Covid lockdowns become that the reality of rising prices for essentials such as food and energy is becoming all to obvious, and prices are beginning to explode upwards.

In Figure 1 above, leading the charge is the US dollar, which should worry us all, because it is everyone else’s reserve currency. And while similar statements emanate from the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, it is those of the Fed’s FOMC, which met this week, that always have global significance.

The FOMC’s problem

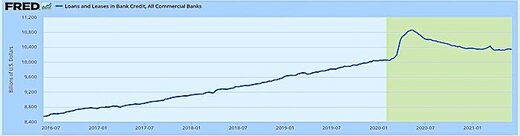

The Fed’s money-printing has continued apace, so much so that severe market distortions are reflecting it, even for those with badly impaired economic vision. As the US economy is re-opening following the easing of covid restrictions, policy planners expected there to be increased demand for money, reflecting the ramping up of consumer goods production to meet demand and therefore of the necessary working capital. But looking at bank credit to non-financials (loans and leases in the Fed’s H.8 table) there is no evidence this is happening. So far, the banks do not appear to be keen to lend or perhaps their customers to borrow, as shown in the St Louis Fred’s chart below.

The worst inflation is not down to the Japanese but to the Anglo-Saxons, as Figure 1 illustrates, which dates from before the central banks’ first introduction of extraordinary measures following the Lehman crisis.

Loans and leases saw an increase ahead of lockdown, when banks recognised that they must bridge their customers’ cash flow, or risk driving them into non-performing territory. Unsold inventory was stacking up, which over the last year has gradually been cleared, leaving little or no product on the shelves while reducing the need for working capital.

But in an economy hooked on money and credit expansion, the Fed had to keep the plates spinning, which it did and still does by goosing financial markets with $120bn of QE every month. For the Fed it is vital that market confidence remains intact, and an unprecedented monthly QE injection had this objective in mind. With bond markets underwritten by the Fed’s bond buying through QE, the US Treasury was able to raise large quantities of money through bond sales in anticipation of an unprecedented level of unfunded spending.

Between them policy planners at the Fed and the US Treasury made an important error. The Keynesians, who show little sympathy with supply-side economics, believed that consumer spending at the end of lockdowns would automatically lead to increased production. Instead, after decades of perfecting just-in-time production methods, businesses have been faced with a lethal combination of continuing supply chain disruptions, higher commodity and raw material prices, and a labour force that appears reluctant to return to work. The assumption that stimulation of consumption would trigger an automatic rebound in supply of products and services turns out to be wide of the mark.

If the banks have been cautious in their lending it was with good reason, and it is hardly surprising that loans and leases in bank credit have failed to increase. Whether it is the banks worried about risk, or in these conditions, businesses seeing no reason to demand more working capital without the production capacity to deploy it is a moot point. But it is wholly consistent with a catastrophic supply-side failure.

For consumers it is rather like getting dressed to the nines to attend a ball only to find there’s no one to dance with.

The liquidity problem was foreseeable

Without the expansion of production, there is an excess of liquidity in the American financial system, which explains why in recent weeks bond yields have fallen and a feeling of deflationary conditions has emerged. It explains a mystery unfathomed by some commentators who only look at the collateral side of reverse repos. The reason outstanding reverse repos have hit a record of $721bn is not due to insufficient collateral in the banking system, but having overcooked it, the Fed sees that there is too much unused liquidity. And making the situation worse, instead of raising money through bond sales, the US Treasury has been drawing down on its balance at the General Account with the Fed — technically putting money into circulation which was not there before.

Since last October, about a trillion dollars have appeared in the money supply in this way. And at the same time, the Fed has issued nearly a further trillion through QE. All this excess liquidity with a banking system constrained by lack of balance sheet capacity threatens that market interest rates would turn negative…

If market rates went negative, money market funds would almost certainly “break the buck” leading to a crisis at the heart of the financial system for this $4.5 trillion market, whose investors have been led to understand that their funds are safe. The Fed responded to these concerns by fixing the reverse repo rate at 0.05% in yesterday’s FOMC statement.

It is little wonder that the Fed has had to claw some of this liquidity back, for fear of driving interest rates into negative territory. This situation was foreshadowed in a Goldmoney article last February, when I pointed out that there was a risk these events would lead to market-imposed negative interest rates, particularly if the Fed did not extend the temporary suspension of the supplementary leverage ratio and increase the counterparty limit of $30bn on its reverse repo facility. It did increase the RRP limit to $80bn but did not extend the SLR suspension.

Back in February and in the following month at the quarter-end, we were able to see these conditions evolving. The difference, for the Fed at least, was their blindness to supply-side issues, and that price inflation would rapidly accelerate beyond the bounds of statistical control. And with independent analysts, such as John Williams at Shadowstats.com estimating that price inflation is now over 11% annually, the distortion in financial markets awash with excess liquidity at zero interest rates is increasingly destabilising.

The question for the Fed now is that with all their policy levers having failed, how should they proceed? If they taper, the stock market will almost certainly crash, undermining the Fed’s cherished policy of using the stock market to keep everyone optimistic. If they take the lead in raising interest rates, that goes against Keynesian religion and is simply beyond contemplation. That is why policy default in yesterday’s FOMC statement was to give the briefest of nods to the inflation threat and reaffirm the conviction that left alone the problem will go away.

Interest rates should be rising

The signal being received by the policy planners from the apparent lack of demand for money is that deflation has the upper hand, an argument they are likely to milk for all its worth: the idea that there is too much money in the system rarely occurs to them. But with M1 money supply standing at $19 trillion in a $20 trillion economy…

Admittedly, the statisticians bolstered M1 last February by shifting most of M2 into it, but the point remains that there is far too much money in the economy relative to genuine economic activity. There is a latency in its absorption, which means that the liquidity bulge is only temporary before markets adjust for it. The adjustment is emerging through rising prices because in the absence of an increase in savings it is the purchasing power of the currency that inevitably compensates for excess monetary supply over the true demand for it.

There seems to be confusion in the minds of macroeconomists on this issue. At a time when the purchasing power of the dollar is set to fall, establishment thinking in the markets appears to be signalling a decline in economic activity consistent with deflationary conditions. That being the case, neo-Keynesians argue that declining demand leads to falling prices; or put another way a rise in the dollar’s purchasing power. The issue, as often is the case, is defining deflation. If it exists — and that is open to question — it implies a contraction in the total quantity of money and credit, and the consequences that follow, which is not the condition that is faced. And we can reasonably assume that any further tendency for bank credit to non-financial borrowers to contract will be more than countered by increases in fiscal deficits financed by monetary expansion.

For the state to become the motor driving the economy when free markets are deemed to fail is basic Keynesian philosophy. Meanwhile, as if to drive the deflation argument home, recently we have seen a steadying in the dollar’s trade weighted index of over 2% above recent lows (yesterday the TWI rose 0.75%) and a recent fall in bond yields. Figure 2 charts the 10-year US Treasury bond yield and figure 3 shows the dollar’s TWI.

No doubt, the Fed and Fed watchers are closely following these charts. For them, it is probably comforting that the markets do not appear to take an inflation threat as seriously as the few independent commentators who have warned that interest rates will be forced to rise later this year — and not later in 2022 as the Trimmers in the FOMC have now suggested. But the dispassionate view is that the inflation threat is not only real, but when markets wake up to it there is nothing the Fed nor the US Treasury can do to prevent the consequences.

The underlying reality is that without interest rates being maintained at a rate which discourages foreign holders from selling the dollar either for other currencies or for “real assets” such as the commodities and raw materials used in the course of production, the purchasing power of the dollar has the potential to fall dramatically. This phenomenon is already visible in commodity prices, as Figure 4 clearly illustrates.

Since the Fed reduced interest rates to the zero bound in March 2020 and began QE of $120bn every month, the near doubling of this index tells us that the purchasing power of the dollar in terms of commodities has nearly halved. The fact that the dollar has only declined by about 13.7% against the euro (the largest component of its TWI) indicates that the euro has also lost purchasing power, though not to the same extent as the dollar. For the Fed to claim that inflation is merely transitory is either being disingenuous or ignorant of the theories of exchange — it matters not which.

The Fed is already judged guilty in the court of commodity markets. It is hard to see how it will not similarly be judged by other forms of evidence, being the broader consequences of inflationary monetary policies. With foreign ownership of dollar denominated financial assets and cash deposits at $30 trillion, the dollar is more exposed than any other significant currency to the judgement of the foreign exchanges. Consequently, as it becomes clear to foreigners that the overweighting of dollars is no longer safe, the downside of the Triffin dilemma will become manifest.

Triffin described the situation where the issuer of a reserve currency has to deploy ultimately destructive inflationary policies to supply the world’s demand for it, until a currency crisis inevitably leads to its ultimate rejection. The last such crisis was also ahead of a period of escalating dollar inflation, commencing with the failure of the London gold pool in the late 1960s, followed by the abandonment of the Bretton Woods agreement in August 1971 and the roaring price inflation of the 1970s decade.

Today, unprecedented market distortions coupled with the accumulation of dishonest statistics and Keynesian cluelessness is considerably more dangerous than the failure of the London gold pool and the ending of Bretton Woods. Therefore, when Triffin’s downside for the dollar materialises this time, we can expect the deterioration to be sudden and very public. That appears to describe the cliff-edge upon which we now sit.

Monetarists who understand, as Milton Friedman put it, that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, have just half the story. Their understanding is that the relationship between money and subsequent prices is essentially mechanistic. It is not, as the following well documented example attests. Between April 1919 and March 1923, the German government’s cumulative increase in debt, i.e., the difference between revenues and spending financed by a mixture of savings and monetary inflation, measured in gold marks was an increase of 203%. Yet the unbacked paper marks in circulation increased 207 times over the same timescale, and its purchasing power declined from three paper marks to one gold mark, to 5,047 to one. So, an increase in the cumulative, mostly inflation-financed government spending of 203% had a disproportionately destabilising effect on the currency.

Only then did the final collapse in the paper mark begin, taking it to one trillion paper marks to one gold mark in about six months. This was what the Austrian economist von Mises termed the crack-up boom; the phenomenon whereby the general public, finally realising that the state’s paper currency was never going to stabilise, finally dumped it for anything, needed or not.

The lesson from this and many other sorry tales involving state-issued currencies, backed by nothing more than a dwindling faith in the issuer, is that the collapse of a currency is always unexpected by its users, and when it happens can be swift. Today, a market awakening will have to accommodate a stock market crisis, a bond market crisis and the realisation that all financial assets are badly mispriced. If John Williams at Shadowstats is right, and undoubtedly, he is, then a fall in the dollar’s purchasing power currently annualised at over 11% will require a suitable interest rate to compensate foreign holders. But even a move of less than half that will take out over-indebted corporations and force the US Government to accept cuts in spending that it is simply not prepared to make.

Its advisers are Keynesian to a man (or woman). They long ago dismissed classical economic theory, and offer no solutions, only more bad advice. The advice is likely to be to chuck more money at the problem, in order to stabilise stock markets, fund the government’s ballooning debt and to subsidise industrial production. They are even likely to opine that a lower dollar stimulates economic activity and perhaps that price controls should be introduced.

Along with dollar-denominated assets being sold by foreigners, the currency is set to continue its collapse. As we might have seen with the resignation of the Bank of England’s chief economist, unpalatable truths will continue to be rejected. And as the purchasing power of the currency declines, public demand for it will increase, not because it is wanted per se, but because its purchasing power is declining faster than it is being pushed into circulation and more is required to cover even diminishing real levels of spending.

This is what kept the printing pressings working 24/7 in Germany in 1923. With electronic money, there is no physical restraint, and the expansion of money supply will take on a life of its own, potentially speeding up the process. What took place between May and November 1923 when the paper mark finally hit the wall could easily be compressed into a matter of just a few weeks.