From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 16 No 4 (Aug 2022)

We should be cautious of prophecies that claim we are on a path of infinite political progress or infinite economic growth – or, conversely, headed toward civilisational collapse.

Things are more complicated, and opportunities remain for creating interesting new cultural movements and for personal transcendence and integration (though perhaps not for those who are determined to conform to some outdated societal mould).

A century ago, the German intellectual Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) argued that civilisations are organic and, like plants, they take root, blossom, whither, and die. According to Spengler, the West is now in its dying phase. His thesis was countered by another German thinker, Jean Gebser (1905-1973), who argued that human consciousness evolved through the emergence of new stages. The previous stages remained part of the psyche but were superseded. These stages (the archaic, magic, mythical, and mental) were characterised by new developments in language, art, and even perception (e.g., the development of perspective in art).

Perhaps more important was the thesis of British historian Arnold Toynbee (who was influenced by Spengler). While Spengler preferred “culture” to its more developed and complicated phase – civilisation – Toynbee believed that the former type of society preserved itself by worshipping the dead and sticking, unquestioningly, to the rules that the ancestors had laid down. But a civilisation, Toynbee argued, constantly renews itself through the actions of a “creative minority” – a small group of individuals who think differently and create new culture. (One such creative minority was the Beatniks of the 1950s, who attempted to live authentically, creatively, and spiritually in the context of a West in decline, introducing many Americans to Eastern religion, alternative spirituality, and psychedelics.)

Spengler’s thesis can be detected in the warnings of feminist social critic and author Camille Paglia. She suggested a few years ago that America may well be in a stage of decline and cited the transgender movement as proof, suggesting that transgenderism gains popularity in the “late phases of culture, as a civilisation is starting to unravel,” e.g., the late Roman Empire, the Weimar Republic, and so on.1 The people of such societies, says Paglia, think of themselves as very sophisticated, but yet, out on the margins of society, or just beyond the borders of the state, those – from the Hun to ISIS – “convinced of the power of heroic masculinity” are gathering, waiting to strike.

Paglia is not the first to contrast the militant jihadist with young, effeminate Western men and modern Western culture that “no longer believes in itself.” Nor is she the only one worrying about the emergence of hyper-masculine men, though she is unusual, as a feminist and progressive of sorts, for her criticism of the latest political fads. The target of the more “sophisticated” members of our societies tend to be those representing traditional culture, pro-masculinity groups, or groups advocating physical and mental strength. But Paglia is an actual thinker, of course, and not merely another establishment apologist posing as one.

Disintegration

Who are the barbarians? When we look at television and movies today, we see that men are not infrequently portrayed as clueless, weak, ignorant, stupid, cowardly, or thuggish. Heroes are dead. And we do not need strength and courage. Of course, this angers a lot of men – especially in the “men’s rights” movement – and some are convinced that it’s a Hollywood conspiracy to deracinate masculinity. But, let’s be honest, if these images of men caught on, it is because that was the experience that so many people had of men.

I have spoken to men across the United States, and the vast majority told me their father gave them no real attention or guidance growing up or that he was a workaholic, an alcoholic, a “yes man,” a womaniser, a bully, or worse. If they received guidance on how to behave, it usually came from their mother or their first real girlfriend. Unsurprisingly, many young men feel resentment toward older men in power and are suspicious of “masculinity” (a term they equate with working too much, bullying, watching sport, hitting on women, and talking nonsense).

Beyond which team to support and which political party to cheer for, the stock advice from fathers to their male children is often little more than “get good grades and get a good job” – or at least some kind of job – or “don’t do what I do; do what I say.” This doesn’t really grab most young men as a satisfactory plan for life. A lot of pain in men goes unnoticed.

I mentioned the portrayal of men and women on television. In one op-ed a few years ago, the ‘90s sitcom Friends was blamed for the downfall of Western civilisation.2 For the op-ed writer, Ross was the show’s hero – or, at least, he should have been. He was an intellectual (or at least intelligent). But he was boring in comparison to the rest of the Friends gang. As such, society was given the message that intelligence is bad. He got the girl he deserved, the writer tells us: “Rachel, the one who shops.”

Apparently, not all Rosses are boring. While the writer assures us that there is now a “resistance” forming, made up of “new Rosses” – people of “grit” who are “hiding” in art museums, chess clubs, and so on – Rosses aren’t going to save civilisation from the nightmare Paglia imagines – its collapse and takeover by new barbarians. In real life, Rachel (by which I mean the actress Jennifer Aniston) married (and then divorced) Brad Pitt.

We don’t need to pick through Aniston’s off-screen love life and its ups and downs to know that the dithering and undynamic Ross wouldn’t have got a look-in with Rachel. And, frankly, why should he? He wanted a woman that was, physically, well out of his league. He could have gone across the hall and asked Joey for some pointers on working out and then set to work improving himself physically – but he didn’t. And, unlike most people, he didn’t want to, or couldn’t, adapt his conversation to his friends, either.

Ross (and the Friends gang as a whole) reflects the West’s compartmentalisation of people into types: the intellectual (the intellect), the jock (the body), the artistic dropout (the soul), the Democrat, the Republican, the independent, the non-binary, the genderqueer, the two-spirit, and so on, and so on. (Effectively, Friends is a comedic Planet of the Apes without the ape costumes or post-apocalyptic NYC backdrop.) And while compartmentalisation may have helped us create civilisation, it is now contributing to its disintegration.

Revolt Against The Shrinking Brain

Rosses may represent a clumsy resistance to the dumbing down of society. Some of those becoming transgender may, as Paglia suggests, be the sort of people who would have become Beatniks or Hippies in decades past and might be rebelling against the very limited, clichéd 1950s-type notions of gender (pushed in some online “masculinity” and politically conservative circles). Men’s rights groups may be an angry resistance to men not being taken very seriously on a range of issues (e.g., divorce and child custody). And as Paglia suggests, culture may be “starting to unravel” into different types, none of them whole in themselves. But opportunities remain.

As Paglia notes, that opportunity is open to those who would destroy us and take our liberty away. But that is not the final word. Opportunities are open, too, to the creative, adaptable, and integrated. (The integrated are entirely opposite to the mass of compartmentalised individuals: Rosses, Joeys, and Rachels, etc.)

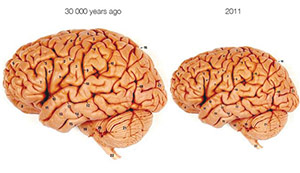

The human (genus Homo) brain quadrupled in size over six million years but, strangely, appears to have decreased in size since the last Ice Age. Diet and environmental factors are blamed. A more recent hypothesis suggests that human brain shrinkage occurred in response to the expansion of our societies and the need for greater compartmentalisation of tasks to sustain and develop those societies (i.e., civilisations).

Jeremy M. DeSilva et al. note that “brain differentiation can occur in association with division of labor in the absence of striking changes in body size, illustrating how selection may have operated in humans as social groups increased in size.”3

Formed into large and increasingly complex organisations, human beings needed specialists, not generalists. It needed some people to focus on medicine and others to focus on engineering, some to focus on creating art and others to focus on fighting wars, and so on, effectively distributing functions throughout the community. DeSilva says, “multiple brains contribute to the emergence of collective intelligence.”

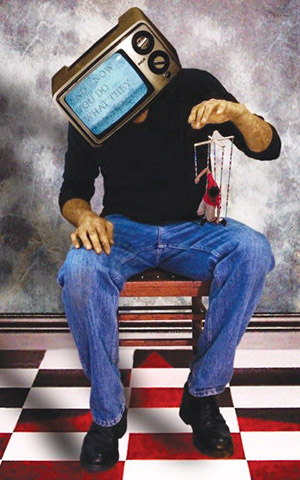

The collective brain is most visible in the realm of politics. The ideas of a particular movement are thought up by a handful of individuals at most (these original thinkers are usually dead before their ideas catch on). The average voter and political fanatic (the compartmentalised individual) merely receives these ideas and passes them along, acting as a node in a network. He believes them to be “true” because, unaware of their history, the ideas appear to have emerged out of nowhere, suddenly to be accepted by everyone (every other node) around him. Nevertheless, the more the compartmentalised individual is convinced he arrived at his own conclusions, the more likely he will parrot the latest political mantra, spreading the message to other nodes. And tied into his self-image and survival as a node in a network – if the information is challenged or shown to be false, his response is usually anger, outrage, and ad hominem accusations. In authoritarian societies, detractors are prosecuted and either imprisoned or executed. Typically, though, such societies fail.

Let’s consider Western civilisation as a brain (or an organism). The current obsession with “diversity and inclusion” can be regarded not as an expression of a moral conviction (as it is presented) but as a survival mechanism: i.e., as an attempt to expand the network so that new nodes can pass along new information about possible threats from outside as well as new opportunities. Racial, sexual, gender and religious diversity within the workforce is often presented as a way for companies to gain an advantage over competition (which seems amoral at best). And notably, although the registration of patents (probably the most concrete marker of innovation in any society) has gone up in the United States over the last few decades, half of these were registered by foreign-born inventors.4 Everyone’s favourite entrepreneur, Elon Musk – founder of Tesla, SpaceX, and Paypal – immigrated from South Africa, first to Canada and then to the US.

Renewal & Reintegration

The integrated individual – capable of thinking, creating, and problem-solving – might be a throw-back to a time before civilisation, but that individual is essential to its survival and renewal. He, or she, is one of Toynbee’s creative minority. Even in more ordinary lines of work, in a fast-changing society, developing different skills and interests will be an advantage and might be essential to remaining relevant to the economy. “Holding a solid grasp of many concepts or decent proficiency in multiple skills,” says Forbes, “can allow for flexibility, in a life and career.”5

But there are things more essential to life and the human spirit than commerce, of course, though it may be crucial both to the individual and their society. The Renaissance saw a renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman thought and classical learning, as well as new developments in the arts (such as perspective in painting) and sciences. And epitomised by Leonardo DaVinci (artist and inventor) and, perhaps, more so, by Leon Battista Alberti (architect, mathematician, scientist, painter, poet, expert horseman, and a man keen to demonstrate his physical prowess). The notion of the Uomo Universale (“Universal Man,” usually called the “Renaissance Man” today) was born during this time.

We can, of course, find such integrated human beings in different times and places. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato was also a wrestler and believed that youths should be educated through philosophy, music, and wrestling. In Shi‘i Islam, ‘Ali is regarded as both the ideal warrior and ideal mystic and as the exemplar of futuwwa (the Muslim code of “chivalry” or, more literally, “young manhood”). The samurai warrior Miyamoto Musashi was also a renowned painter and calligrapher, and Viking warrior Egill Skallagrímsson was also a renowned poet.

Closer to our own time, we find the Renaissance Man turning up primarily in, or on the margins of the occult, with the ability to break the taboos of a spiritually disintegrating culture being, perhaps, necessary to begin the journey towards personal reintegration. Rudolf Steiner was a mystic, educator, painter, author, and architect. G. I. Gurdjieff was a mystic, hypnotist, and (sacred) dance teacher. Carl Jung was both a pioneer of psychoanalysis as well as an artist and visionary author.

Known primarily as a ceremonial magician, author (fiction and non-fiction), and founder of his own religion (Thelema), Aleister Crowley was also a boxer, mountaineer, adventurer, painter, and poet. If we take half his accomplishments, he is a clichéd “man’s man.” If we take the other half, he is an effeminate, dandyish “girly man.” But, as he advised his adepts, in himself he managed to embrace and develop the “Angel” and the “Demon” – what society might call the “male” and the “female,” the “left brain” and the “right brain,” the body and the spirit, etc.

Modern culture has hemmed us in. Today, painting, poetry, calligraphy, etc., are all seen as “feminine” or “girly.” In contrast to Musashi or Skallagrímsson, modern-day “real men” do not write poetry. In fact, “real men” don’t seem to do much at all. Whether we like it or not, in part, it is against the backdrop of fatherless families and men more interested in gaming and chasing women than in mental, physical, spiritual, and cultural self-development, that the pro-transgender, pro-pan-gender, pro-gender-fluid movement is reacting. And we must agree with them that the 20th-century clichés of gender – the compartmentalised man or woman, individuals who act merely as nodes, passively absorbing and regurgitating whatever they hear – are inseparable from the disintegration of the West and the lack of energy it displays in the arts, philosophy, and other areas of culture.

We mentioned Toynbee’s belief that civilisations differ from cultures by constantly renewing themselves through the “creative minority.” Perhaps the best example of a renewal is the Renaissance (literally “Rebirth”) which we already mentioned. But there have been other, smaller revivals, such as artistic movements (Cubism, Surrealism, etc.) and musical movements (Punk, Hip-Hop, etc.). It might even be argued that the emergence of transgenderism, pangenderism, and gender-fluidism into the mainstream is part of a revival (perhaps emanating from the unconscious of the collective intelligence) of the shamanic (since shamans often wore the clothes of the opposite gender and were regarded as neither or both male and female) and, as such, as part of a centuries-long occult revival that includes, at its softer edges, the now virtually omnipresent New Thought movement and New Age spirituality.

We mentioned the union of the mystic and the warrior in the figure of ‘Ali, as well as Plato, the philosopher and wrestler. The average person might remain a node in a network of the collective brain, merely absorbing and transmitting ideas to others without ever questioning those ideas, even as the disintegration of their society continues. A new Renaissance will only be brought about by the work of creative minorities. And, today, in a time of increasing hostility towards the body (particularly as an embodiment of strength or beauty), when life is increasing online and virtual, and thinking is increasingly done for us (or against us) by algorithms and artificial intelligence, such a minority must work to elevate the physical body and reintegrate it (as Plato suggested, with his schema of music, philosophy, and wrestling) with the mind and spirit. We must be part-barbarian and part-sophisticated cultural thinker and creator.

The future is uncertain but it remains open to the integrated – to those who push forward in different ways, creating new art, new ways of thinking, new movements, new rituals, and new routines, all awakening us to a recognition we are more than nodes in a disintegrating network: that inside of each of us burns a barbarian fire – a spirit – for adventure, for struggle against our limits, for strength and beauty, and wholeness.