Alisa Neathery, a young dusky beauty, fragile in her composure, walked to the front of the starkly lit meeting room, holding two things: A photograph of her smiling baby boy Bently, and a moon crescent shaped silver object. I wondered what it was.

She began to speak, and tell her shocking story.

When her son Bently was six months old, she took him in for a round of vaccinations to his local clinic, in Fort Worth, Texas, where she lived then. She had delayed giving him his two-month shots, so his immune system could develop a bit more, and she felt confident that he would fare better now that he was six months old. The pediatrician that day was telling her how important vaccinations were, and how many children died without them in his native country in Africa. He described how mothers would line up to get the shots for their babies, and that many had to have 10 children, just to have a few that survived infancy.

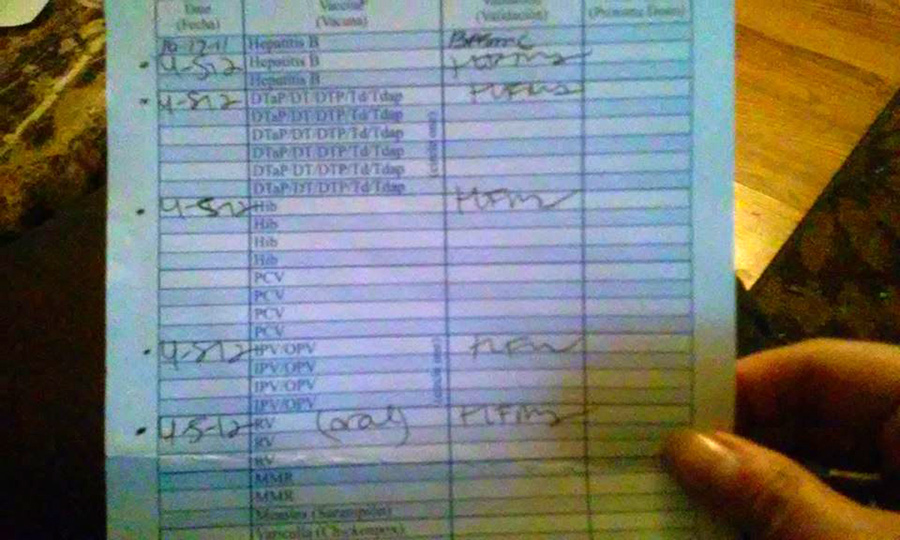

Totally unbeknownst to his mother, Bently received a staggering 13 vaccinations that day, including two triple doses of DTap, Hepatitis B, a polio shot, three oral rotavirus doses, and a pneumococcal pneumonia vaccine. It was all compressed into three shots and one oral dose. It took the nurses half an hour to prepare all the shots Bently received. The pediatrician told Alisa that her boy perfectly healthy—that he showed above average strength in his stomach and legs.

Five days later, he was dead.

Bently died while sleeping on Alisa’s chest in the middle of the day, five days after receiving those 13 innoculations.

Holding up the photograph, Alisa says, trying to steady her voice, “This is Bently, or… was Bently.”

Then she holds up the silver object:

“And this is Bently now,” she says quietly.

Bently died while sleeping on Alisa’s chest in the middle of the day, five days after receiving those 13 innoculations.

When she brought him home that day he was twitching a lot, extremely cranky, no longer making eye contact, and had a red knot on his leg, that was still there when she viewed his body prior to cremation.

“I trusted them,” she said. “I thought this was going to save my son.”

At the back of the room, her now five-year-old daughter Skyler, who was two when Bently died, shifted in her father’s lap and looked over at the table of fluffy cakes.

“He adored us all. He adored his sister and his dad, my husband. He had just learned to say “Mama.” My daughter was there. She looked at him when he said it, and repeated, “Mama?”

In 2010, a study found that the US had the highest infant mortality rate (6.1 out of 1,000 live births) of 28 wealthy industrialized nations. The US also has the highest number of vaccines given to infants.

“There are so many children who have died and been injured by vaccines that sadly, Alisa’s story is very common,” says Nancy Babcock, who runs a Facebook support group called Angel Babies for the parents of children who have died following vaccinations.

“Alisa is a brave soul for sharing her story, and there are so many just like her. It’s heartwrenching.”

“Angel Babies was started by my friend Suzanne who lost her precious boy Tommy. The group immediately got so much attention that she was about to shut it down because she couldn’t stand the grief and I asked her not to and offered to help.”

The group posts photos of the babies alive, then, often, photos of them after they have died, sometimes in small coffins. The parents, usually the mothers, write detailed accounts of what exactly happened, and the timeline is always the same. By some mechanism, the infant brain holds off the toxic assault for a few days, then quite suddenly, the child dies.

Another chilling fact is that SIDS, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, coincides with the infant vaccination schedule—the deaths from SIDS generally occur between 2 and 6 months.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System is a US Government reporting system for vaccine injuries and deaths, funded by taxes on vaccines. It collects some (far from all) reports of vaccine injuries and deaths. Since its inception, it has awarded $2.5 billion to families or individuals, for injuries and/or deaths proven to be caused by vaccinations.

At the same time, rather inexplicably, US health agencies continue to insist that vaccines are in no way linked to SIDS.

Most SIDS deaths occur between 2 and 4 months, which coincides exactly with the peaks of infant vaccination schedules. US health agencies state categorically that SIDS is not caused by vaccines, despite this correlation. But numerous studies run counter to this assertion.

It’s now been three years since Alisa lost her son, and she has finally found the strength to begin to put into words the truth as she knows it, as she lived it. “Vaccines killed my son,” she says, without anger, but also without ambivalence. “I was with him all the time. Every minute. Nobody knew him better than I did. There is no question in my mind.”

Alisa is the kind of parent entertainer Jimmy Kimmel saw fit to mock in a shockingly depraved comedy bit that made the rounds on the Internet, to the disgust of millions. She’s “paranoid,” enough to think vaccines killed her son. As pro-vaxx bullies would have it, Alisa’s message is a threat to the survival of America’s children. But she does it for the same reason all the grieving mothers do it: “Ever since he passed away this has been something that I really wanted to do. If I can help save any life, any child, adult, anybody from going through unnecessary heartache and pain, that is the only consolation I have now.”

Bently’s official cause of death was “SUDS,” or “Sudden, Unexpected, Unexplained Death Syndrome..

The medical examiner told her that he was almost never in his career unable to find a cause of death in a corpse, even one who has decayed outdoors for years—but he could not find a cause of death for Bently.

“‘There’s no reason why he should not be alive,'” were his exact words,” Alisa says.

Adding insult to tragedy, CPS removed Alisa’s older daughter Skyler from her home and placed her with her grandmother for a period of four months while they “investigated.”

Adding insult to tragedy, CPS removed Alisa’s older daughter Skyler from her home and placed her with her grandmother for a period of four months while they “investigated.” These are precisely the intimidation tactics that cause most parents to remain silent after their children die. Alisa herself never protested, never even informed the pediatric clinic, after her son died. “I didn’t want to raise any red flags,” she says.

The most tragic subset of parents are those who are actually charged with the murder of their children and sent to prison—over “shaken baby syndrome.”

Thankfully, Alisa and her husband were at least spared this fate.

Alisa’s story actually has a prelude, a foreshadowing, that makes the story even more startling.

It was a few years prior—she was pregnant with her first child, Skyler, and working. At the salon where Alisa worked as a hair dresser, a colleague got a devastating phone call that sent shock waves through the whole salon. Her baby was home with her boyfriend, who went to check on him, and found him unresponsive in his crib, with blood coming out of his ears and nostrils. His death, at two months, was labeled SIDS.

Alisa recalls, “My thought at the time was, when I have my baby, I want to stay home, and not go to work.” As soon as Skyler was born, Alisa became a stay at home mother.

Our health agencies have convinced mothers that SIDS is caused by positioning on the mattress, and/or co-sleeping, so that was, quite naturally, what Alisa focused on. But Bently died, ironically, while napping on top of her chest.

It was April 10, 2012, in the late afternoon. Alisa had been cleaning the house all morning, and both of her children had been especially well behaved. “Skyler was sitting with him in front of the TV, playing with him and keeping him entertained while I got the cleaning done. Justin had just come in for lunch.”

Alisa felt sleepy, and sat down in a reclining chair, as Bently slept on her chest. She awoke to her husband Justin saying, “The baby is not breathing. Wake up.”

“I couldn’t comprehend what he was telling me,” she recalls. The baby was still warm. “Alisa, call 911,” he shouted, as he began CPR.

The next thing Alisa remembers, she was laying outside in the grass screaming, as 12 paramedics and two fire trucks arrived. In her state of hysteria, she could not bring herself to go back inside the house. “I was waiting to hear him cry,” she says.

In the ambulance, she was told her son was brain dead. He had been fine just two hours earlier. It was 4:15 pm.

They got to the hospital, and shortly thereafter, four chaplains came to talk to her. “They said they had bad news and I just fell to the floor. I was absolutely out of my mind. They had to give me Thorazine and take me to another hospital. The Thorazine knocked me out, unconscious. I woke up on my mom’s couch the next day and just began to scream, realizing it was not a dream. I was just screaming and crying. It was the worst physical pain imaginable. Every morning I woke up screaming. I wanted to see him again and hold him again. I sat in my daughter’s room for weeks and weeks reading the Bible and just crying. I considered suicide but I just kept telling myself if I did that I would never see him again.”

Alisa descended into a dark abyss of spiraling grief. She could not be left alone, so her husband had to quit his job and stay home with her. Money was scarce, and they had to face the costs of funeral arrangements, which fortunately their church collected for them. “They let us build his little casket, which saved us $500. My husband built the casket that Bently was cremated in.”

Alisa only returned to the pediatrician’s office once, still in deep shock; she only asked for Bently’s medical records, which somebody had advised her to do.

In the mid-1980s, the US Government indemnified the vaccine industry which complained it was losing too much money in a typhoon of product liability lawsuits, by creating a special and separate “Vaccine Court” (The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program) where only a minority of cases are heard.

In this separate universe, however, it has been acknowledged, legally, again and again, that vaccines can cause brain injury, autism, and death.*

Alisa had one true friend and ally during those first few frightful weeks of acute grief: Her former colleague, April, who had also lost her baby years prior. “She knew what I was going through. She’d been there.” April came over every day, and sat with Alisa.

One day, Alisa sensed something in April’s facial expression. She wasn’t sure what she wanted to say but she falteringly said, “Have you thought about the vaccines?” The two began to discuss the similarities in their stories. “Something told me to mention vaccines to you,” April told Alisa, though she herself had never pursued the matter after her son’s death. “It was just one of those weird little things,” Alisa says.

It was April who urged Alisa to get Bently’s medical records, where it was confirmed that he received 13 vaccinations, in one visit. With all their energies focused on both financial and emotional survival, the family did not pursue any legal action.

In 2014, to get away from all the painful memories, they moved to Massachusets, then to upstate New York, where they live now.

Alisa also, astonishingly, lost her grandmother, shortly after she got a flu shot.

Today, she immerses herself in self-healing modalities, and positive affirmations, as she struggles to move forward, and accept what happened. She posts pictures of Bently on Facebook, along with loving messages, and on the third anniversary of his death, the family got mylar balloons with his name that they released into the sky. They don’t make mylar balloons, or words, for that matter, that could ever be the right words for something like this. Mylar balloons are supposed to be for the living, for joyous occasions. I go visit Alisa’s Facebook page to look at the balloons. I can see the text of three of them. They say:

“You’re so special”, “Baby Boy”—and most heartbreaking of all—”It’s your day.”

Note: If you’d like to make a donation to Alisa Neathery and her family, they have a GoFundme page here.

– Celia Farber